Labor – creation – action and reflections on the human condition

March 4, 2019

Labor – creation – action and reflections on the human condition

Notes on Lisa Stenmark’s lecture on Hannah Arendt’s philosophy

Hoang Phong Tuan

The problem of modern society is that people do not understand and cannot control what they do, losing the ability to act to produce new things. Can we recognize and overcome these limitations?

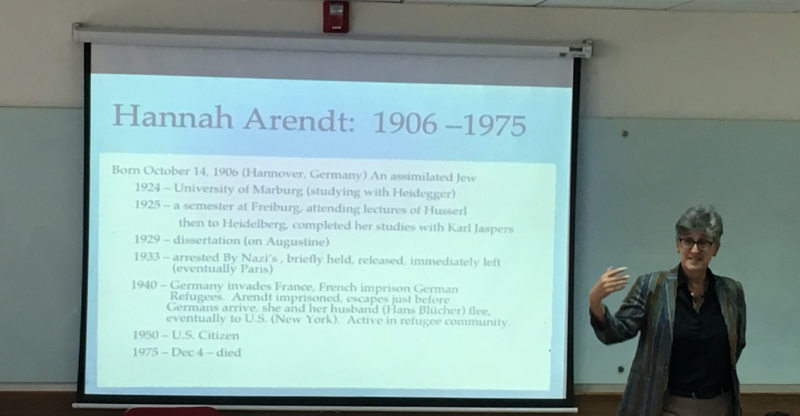

American philosophy researcher Lisa Stenmark introduced philosopher Hannah Arendt’s perspective on labor-creation-action, thereby evoking thoughts about human conditions in modern society.

Labor – creation – action are parts of active life

Labor is the production of objects for consumption. It is essential, individual, and cyclical. People will get sick and starve if they do not clean the house and make food to survive, these activities are associated with a familiar family living environment and are close to the person. But labor seen from this perspective only satisfies direct and temporary needs. To live well, people also create.

Artifacts are the creation of long-lasting, stable objects. The result of these creative activities is the world in which we live: the house where we live, the bridge curved like a new moon across a small river, the road with rows of tall trees shading the way home. The world of artifacts is the space in which we live and remember, creating a place for human activities. Therefore, it is also a world of culture, history, and humanity. However, the logic of this created world is purposeful and instrumental, and its characteristic is anonymity and impersonality. We cannot determine the individuality of humans in that world of countless artifacts. But humans need more than an anonymous world, so humans also act to create and locate their individuality.

Action is what we do with and between others, thereby positioning ourselves. Action has uniqueness, individuality, and freedom. I can take action to create something new and different. When Achilles asked his mother if he should go to war or stay at home, the mother replied, if you stay at home, you will have a family, and children, and when you die, your relatives will remember you, but when those When my body dies, no one remembers me. If you go to war, you will also die, but your name will live on forever. Going to war is taking action, doing something new to change this world and create history, a history from the individual. But the logic of action is unpredictable and irreversible. It can push people into an endless chain of impacts and consequences. Therefore, people need forgiveness and promises. This is what Arendt calls the politics of promise.

The politics of promise and non-violence in action

Speaker Stenmark gave an easy-to-understand example of the politics of promise in Arendt’s conception. Her house has a small garden, next door is a neighbor’s house. But one day, when she came home, she suddenly saw that her neighbor had built a high wooden wall, blocking the wind and sunlight from shining into her garden. She could have reacted and called the police. Instead, she took a cocktail to his house and asked about his intentions in building the fence, only to later understand that his wife was about to give birth and was worried that the baby would run away and play around in the neighborhood. garden. Finally, there was a solution that suited both sides’ wishes: the fence would be lowered so as not to block the wind or block the sun.

Speaker Senmark analyzes that in this exchange she acted based on the promise of the non-violence of the action. She did not create a corresponding response, but chose another action, producing a different perspective on the situation to control the uncertainty of the action. The politics of the promise of freedom from violence and rule. It begins with our awareness that there are many different possibilities to initiate an action from a new perspective, it also creates a belief that others can also do something good by the action. This is our new one. And through that collaboration, we create a better living world, in which people can choose different perspectives to act without using violence.

Feedback and a personal impression

Stenmark’s presentations prompted the audience to reflect on human actions in modern society and the in-depth issues of Arendt’s philosophy. A university lecturer questioned whether the purpose of the action is to be known or for the sake of the action itself, using the example of Achilles’ choice. The speaker replied that we cannot distinguish and do not need to distinguish that, typically the soldiers who fought for the national liberation revolution in Vietnam, acted because they wanted to be famous. Stenmark concluded: “I don’t believe they act to gain fame.” The presentation ended well beyond the time allowed, but many listeners still stayed to discuss more about the ideas suggested by the presentation.

Stepping outside the lecture room and suddenly hearing greetings from a few students, I suddenly realized that the desire for knowledge is still present in young people of modern society. That is perhaps the foundation for us to be able to create something new with faith in human abilities and freedom of action.